securing passwords in the workplace

summary

How you handle your organization’s information is not just about what cloud drive you use. It begins with how you handle access. Here, I’m going to outline why you should use a password manager to improve your password management as a starting point for improving your organization’s digital practices.

This is part of a series of articles that explore practices and tools to improve your work as a leader in an increasingly complex digital world.

how not to do it

Let’s start with how not to do it.

Let’s say you’ve never really set email up properly in your organization. You only have a few email addresses, including a “catch-all” that several people have access to. We’ll call it “[email protected].” You have access, so does an admin, the treasurer… actually, you’re not sure how many people have access to this email address. But, the organization’s credit card uses it, as well as your banking, and also… well, now that you think about it, you have no idea where else that email address is used.

Also, the password is short. It’s around 10 characters long; it was set up by a prior admin, and you’re still using the same password. It’s not too hard to remember, because it is basically your organization name, but with a few changes to make it hard to guess. The password is w0rkpLACE!, now that you think about it. But is it secure?

what is wrong with this picture

Let’s make a list, in no particular order. Everything in this list is bad, and I’m not going to try and rank these anti-practices. Every one of them is a threat surface for your organization and everyone who works with you.

- You do not know what accounts use this email address. Because email is an important part of identity and account recovery, not knowing where the email address is used means you don’t know what is at risk. Is your organization’s banking attached to that address? Email? Web hosting?

- You do not put limits on how and where accounts are used. Do you trust everyone? Of course you do. Do all of them know how to avoid scams and viruses online? Do any of them use Facebook or any other apps on their phone along with this account—apps that will happily siphon in information and other addresses without permission? Who has your organization exposed to risk or threat because of bad operational security with a single email address?

- You do not know who has access to what. You realize your previous admin probably still has access to everything… and, you know the treasurer does… but, did the intern need access last year? You’ve now shared it with the new hire… hm. Actually, you have no idea who has access, because you shared the password in an email to someone. So, they could have chosen to share it to anyone they felt could be trusted, too. This means you actually do not know who has access, or to what.

- You are worried about changing the password. So many people need access to this account and the accounts attached to it. You know the password isn’t great, but… ugh. How are you going to make that change?

To be clear:

- You don’t know what accounts use the address.

- You don’t have any guidelines for how/where it should be used.

- You don’t know who has what access.

- You are afraid to change the password, because of all of the above… none of which are good.

how to dig out

Fortunately, it is possible to dig out of this situation.

I recommend four things:

- Change how email addresses and accounts are handled.

- Get a password manager.

- Use two-factor authentication.

- Document your practices

I’ll take them in turn.

add some email addresses

If you’re doing all of your organization’s work off of one email address/one account, you’re putting a lot of risk in one place. That is, if you have one address ([email protected]) and it is tied to a single Gmail account, that means that account is your organization, digitally speaking. Single points of failure are bad, so we’re going to try and unpack that.

- If you have things like social media or web accounts (e.g. web hosting, instagram, Bluesky, etc.), then you should probably set up an account called

[email protected]. All of your digital/social accounts should use that address. - If you have things like credit cards, bank accounts, and the like, they should be on one account.

[email protected], oraccounting, orbursar… whatever you decide is appropriate. Keep the financials separate from day-to-day operations and your social media. - If you have office operations, keep your

office@account. Perhaps that is where HR things go, or perhapshr@needs to be its own inbox as well.

Once you have split things up, you now have a situation where the access and passwords for social media are all managed by one person (perhaps), and they are bound to one address that is all about the social media. You have banking separated out into the space it belongs, and only people with need-to-know about finances (and the authority to interact with your finances) have access there. Finally, you still have a “catch-all” in your operational email account (office@...), but you’re no longer mixing all of your operations into one space.

It will take time to shift these accounts around, but you start by setting up the email accounts and securing them in two ways:

- Using strong passwords.

- Using two-factor authentication (2FA)

use strong passwords

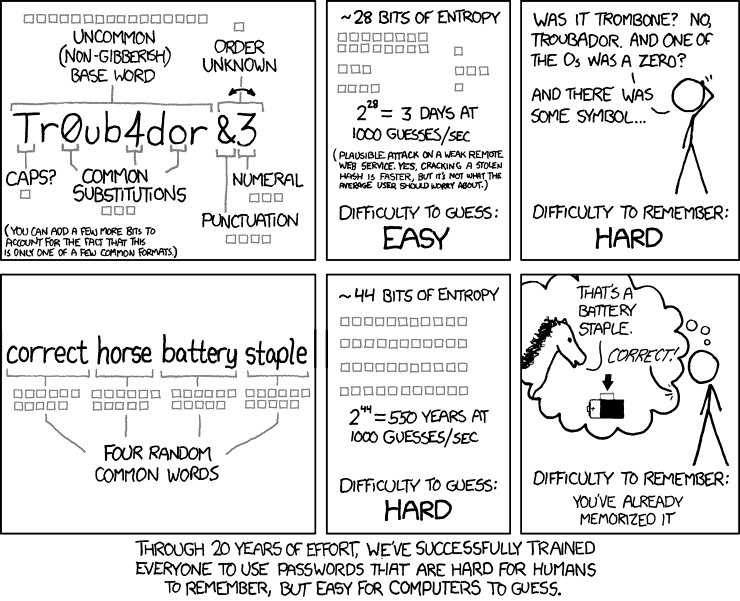

Here’s the rule of strong passwords, in one comic:

Randall Monroe, author of XKCD, makes clear: your seemingly “random” password does not cut the mustard. What you need is a long phrase, because password security is about length. Rob Black, a fractional CISO (think part-time Chief Information Security Officer for hire) has a nice article that goes into more depth about this. Read it.

I’m highlighting the fact that you should use strong passwords, and you should do it with a password manager. This is the same thing that Rob says. (Perhaps I should be a fractional CTO/COO, too?) NIST—government boffins—even say that it really is length that matters.

Intel has a nice animation on this. The longer the password, the harder it is for someone to guess/attack the password.

You could use diceware to generate your passwords, and you’d be doing OK. But, you’d probably be writing those passwords down somewhere, or still be sharing them via email. I’m going to recommend going a bit further.

use a password manager

A password manager does a few things for you.

- It lets you remember one secure password, and protects all the others with it.

- It can generate secure passwords for every site you visit, so you never reuse passwords. That way, a breach of one of your accounts does not endanger all your others.

- It lets you securely grant usage of passwords to others, so that teams can access online resources without (insecurely) emailing or sharing those passwords.

Those are the highlights.

I would recommend any one of these:

- Bitwarden has a business plan at $4/person/month.

- 1Password has a team starter pack that grants 10 users access for $20/month ($2/user).

- Proton Pass has a $2/user/month level.

- LastPass is $4/month/person.

All are reputable. I personally use Bitwarden. My workplace uses 1Password. I’ve used LastPass in the past.

Everyone in your organization who has to work with passwords for business reasons should have a password manager.

Many password managers also have a notion of “encrypted notes,” or just “notes.” (They’re all protected the same way your passwords are.) These “notes” are a great place to add additional information about parts of your operations that perhaps require jotting down, but perhaps should not be in a shared GDrive or similar. For example, some accounts have “security questions” that you have to record and be able to answer. Those should be in the password manager, right along with the password. (For bonus points: don’t answer the questions the way they’re asked. If the question is “What street were you born on?”, the answer could be “fried-fish-sandwiches.” The computer does not care what you put in as the street, as long as you can enter it again later. Using strong/random phrases for your secret questions/answers is another layer of security against someone trying to take over your accounts. But, to do it… you have to have those questions and the answers in your password manager!) Either way, use your password manager’s “notes” feature to capture things like billing info and other important information about accounts that you don’t want to record in a more public way.

use 2FA

Some of these password managers have 2FA built in; that’s the funny thing where you have to type in a numebr when you’re logging into websites. These add to security because they change the login from “just a password” to:

- something you know

- something you have

This way, if your password is leaked, it still keeps others from logging in. Why? Because they don’t have the 2FA “token.” And, it is possible for more than one person to have the 2FA token (if needed), so this can still work with groups. But, what matters here is that to secure an account, you need a strong, random password, and you need a second factor.

Many (if not all) of these password managers have a built-in 2FA component. You could use that wherever one is needed, or you could use a separate app like Authy. There are a lot of possible choices in this space; I use Authy and the 2FA built into Bitwarden personally. (As of writing this article, I’m also curious about Ente, which is a libre/open source 2FA app that runs everywhere. But I digress.)

document your practices

A critical step toward creating an organization that has longevity is to document everything you do.

In the case of passwords and account management, you should create a document that is called “Passwords and Account Management.” I’d recommend it be outlined something like the following:

- An introduction to your choice of password manager; perhaps a pointer to a YouTube video for learning.

- Instructions for installing the password manager of choice.

- A list of what accounts you have, and where

- Who has access to which accounts (preferably by role, not by name. That is, document that “Treasurer,” not “Bob” has access to

[email protected]) - Access control rules

- Under what conditions someone is granted access

- … and under what conditions they lose access

- The process by which you add someone to an account (onboarding) and what you do when you end someone’s access (offboarding)

- What to do if you think an account has been compromised

This document should not list your passwords. That is what the password manager is for! Instead, the document should list your organizational/shared accounts. It helps you remember all the things that are hard to remember: knowing that when someone joins they should have access to certain accounts, or when they leave they should be removed, makes it easy to handle change in your organization, and so on. (Also, this is a living document: as you discover new steps you should add to your protocol, do so.) Tracking these things can be as simple as keeping them in this document, or in an associated spreadsheet, where you can add columns for account names, user names, dates, and so on. It’s just a log.

But, knowing these things, and documenting them, means that when change comes for your organization, you’re ready, because you’ve thought about how to handle change, you have a process for it, and you document what is happening in a simple and clear way. None of this has to take large amounts of time… and, certainly, it takes far less time than (say) recovering from a financial loss or data breach due to bad access and account security practices.

next steps

Ultimately, securing your own digital identity, and your workplace’s digital presence, is not “just one thing.” It is a set of practices and a mindset. You create a secure digital workplace by building up ways of doing things that are, taken individually, not so hard to do. But, by layering one practice on top of another, you build a more secure workplace for yourself and everyone you serve.

In this article, I recommended several things:

- Separation of concerns. This is a fundamental security practice. Have one account for the social media stuff, and another account for the finances. Don’t mix-n-match.

- Training and awareness. In order to move to this posture, you’re going to have to develop standard operating protocols, document them, and help people learn to put them into practice. Ultimately, we’re talking about using the right email account for the work they are doing (easy), and learning to use a password manager (easy). It does involve change, which for some people is not “easy,” but it is necessary.

- Backups/resiliency. By moving passwords to a password manager, you eliminate the issue of “all the passwords being on one computer.” Companies like 1Pass and Bitwarden are doing a lot of work to keep your data backed up and secure. If the office computer catches on fire, or is stolen, or has coffee dumped down its guts… well, you can always log into the password manager on another computer. You won’t lose access to your social media, and you won’t lose access to your bank accounts.

- Documentation. Make transparent how you do things by starting to write it down. It doesn’t have to be fancy to start (or ever). But, you do need to have things written down, so that as your organization grows and changes, as people come and go, you have clear guides for how to get things done.

There’s more, but that’s the essence of it.